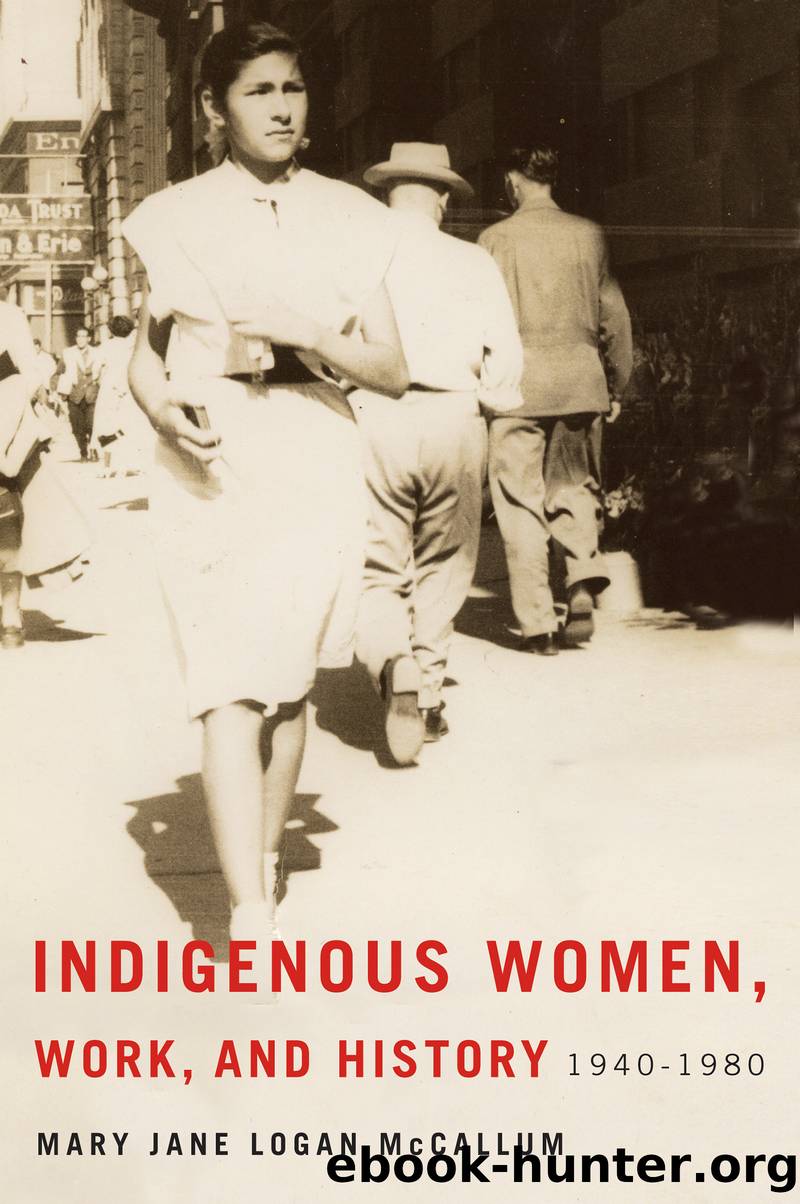

Indigenous Women, Work, and History by Mary Jane Logan McCallum

Author:Mary Jane Logan McCallum

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Manitoba Press

Published: 2014-05-11T16:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER FOUR

Gaining Recognition:

Labour as Activism among Indigenous Nurses

While employment with the Medical Services Branch was clearly racialized and gendered along a hierarchy that severely restricted the positions available to Indigenous women, not all Indigenous health workers fell into the lowest tiers of the system. A small but significant minority of Indigenous nurses also worked for the MSB. These nurses overcame considerable obstacles to attain nursing education and employment and did so in spite of educational policies that prepared Indigenous women for domestic work and generally discouraged them from pursuing higher education. The professional organization of Indigenous nurses in Canada—originally known as the Registered Nurses of Canadian Indian Ancestry (RNCIA)—was a culmination of Indigenous participation in modern health care labour and an important movement of resistance to patterns of Indigenous education and employment that disempowered Indigenous health care workers.

In 1975, Indigenous nurses assembled to hold the first conference of what would become RNCIA, now the Aboriginal Nurses Association of Canada.1 RNCIA was the first organization of Aboriginal professionals in Canada, and its original objectives were unlike those of any other nursing organization. The primary goals of the organization were to improve the health of Aboriginal communities and to position professional Aboriginal nurses as critical components of the Indian health field. The organization also aimed to track and represent Aboriginal people in the profession; to bring to light problems related specifically to MSB nursing, including recruitment and retention of nurses; and to make visible the overwhelming under-representation of Aboriginal nurses in the profession. Another immediate goal of the organization was to promote health professions among Native students and improve their access to education. The founding of the organization was historically significant in terms of Aboriginal nursing, health, labour, and education, but it was not a starting point for the history of Aboriginal nurses. Rather, it was, as Jean Goodwill, a leading Cree RN from Saskatchewan and RNCIA organizer, put it, a “turning point.”2

Currently, literature about RNCIA exists in two different forms. First, there is a significant but isolated collection of the organization’s histories of itself. These histories outline the various efforts of Aboriginal nurses in the areas of Indian health research, community service, and nursing education. Their hagiographic style and tendency to focus on individual nurse profiles, however, make them less informative on the structures of and discourses on nursing, employment, and politics, either in the MSB or in other decolonization projects both within and outside of nursing.3 RNCIA history also exists in brief paragraphs in chapters of books on Canadian nursing. In these, it is discussed as a recent “special interest” development—part of what is seen as a relatively new ethnic diversification in the nursing field—and characterized by a special interest in health problems associated with Aboriginal people.4 In such renditions, RNCIA’s capacity to address larger and longer-standing issues of racial discrimination in health service and health professions is obscured.

Together, these sources reveal the tendency to give only a cursory nod to Indigenous nursing in a story in which they otherwise

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7125)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5415)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5370)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5195)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5178)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4312)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4190)

Never by Ken Follett(3954)

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3772)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3394)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3073)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3029)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2925)

Will by Will Smith(2919)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2845)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2736)